“What is the purpose of your visit to Israel?” an Israeli intelligence officer asked me in an interrogation room at the Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv.

“I’m here to visit my grandmother in the hospital,” I replied.

This was my first time traveling to Israel/Palestine through the airport. On arrival, I was made to wait over six hours for interrogation. I am Palestinian with American citizenship, and although I often travel to Palestine through the Jordan border, the airport is known to discriminate against anyone who has a Palestinian or Arab background. The officer asked for my phone and went through my WhatsApp messages, looking for any correspondence with Palestinian contacts. She continued to question me, asking for proof that my grandmother was indeed in the hospital; asked me about my family history; wanted to know whether I was involved in any activism; made me list every single country I’ve ever lived in or visited in my life. As I reluctantly recounted my life story, I saw her efficiently type up every piece of information I was giving her. I assumed she would add it to the extensive file they already had on me.

I’m a User Experience Designer, and I have spent most of my career designing AI-enabled digital systems. Two core tenets of great design, whether it is for a digital or physical product or for a service, is that it must be easy to use, and it must demonstrate a good understanding of the user behavior. Great design can also be weaponized to undermine the best interest of its users and cause them harm. In the Occupied Palestinian Territories, the system has been meticulously designed to ensure that the people affected by it—Palestinians—are closely surveilled, and to preemptively deter any potential resistance to the status quo of the occupation.

During my visit, I traveled with my mother from the West Bank to Jerusalem every day to visit my grandmother. As a foreign passport holder, I have freedom of movement within Israel, but Palestinians with a West Bank ID, like my mother, have to first apply for a special permit, which is notoriously difficult to obtain. Because of this, my mother and I have opposite experiences traveling throughout the Occupied Territories, and receive differential treatment from soldiers. I could pass through checkpoints in a car and have my passport briefly checked before I’m allowed through while she had to get out of the car and walk through a heavily surveilled and armed structure. She had to wait for hours in line with countless other people as they were herded like cattle through a maze-like enclosure. Cameras stationed at every corner tracked her movements, and facial recognition technology identified who she was. A soldier sitting behind a bullet-proof glass window would yell out for her to approach to verify her ID. Every day presented a new possibility of her being held up or denied entry without explanation. Seeing her undergo this kind of treatment made me wonder what it must have been like for her to experience this humiliation just to be able to visit her dying mother. She is just one example of the millions of Palestinians who are surveilled and treated like potential threats on their daily commute to work or school.

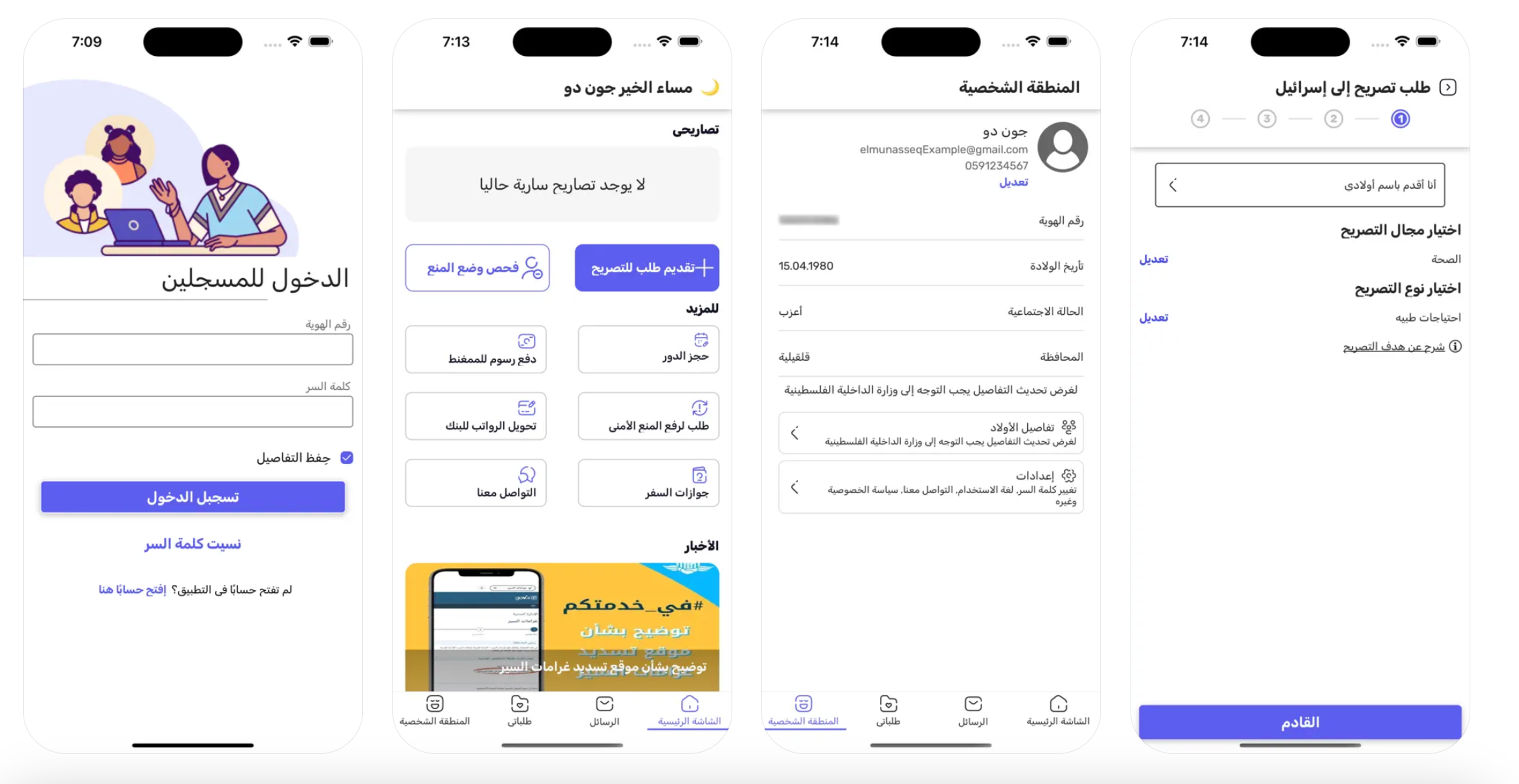

Israel has an incredible success story of using great design to entrench its surveillance system and acquire knowledge of every single detail about the reluctant end users.1 Designed by the military, Israel’s mobile app, Al Munasiq (“The Coordinator”), is a prominent example of an easy-to-use digital interface for data collection. The Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) developed the software, claiming that it would facilitate the process for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, like my mother, to apply for special permits to travel to Israel. With a simple user interface, the app makes it easy to enter information, upload content, and seamlessly request or check the status of the permit, posing as a convenient digital solution for this typically tedious process. What most of the fifty thousand people who have installed the app are not aware of is that they are consenting to granting the military access to all of their device’s personal data, including photos, contacts, location, and message correspondence that can be used “for any purpose” according to the app’s Terms of Service. An Israel-based human rights organization, HaMoked, recognized that this constitutes a severe violation of users’ right to privacy and puts them at risk, and demanded that COGAT change their terms of service.2

Screenshots of Al Munasiq in Apple App Store, Link.

These deceptive design practices are known as dark patterns.3 The app’s misleading interface deceives the user about its invasive terms of service. Israel's Ministry of Agriculture instructed employers to require Palestinian laborers to fill out a health declaration on the app prior to entering Israel for work. Most of these workers, who have no economic alternative but to seek work permits in Israel, are forced to use the app and unknowingly sign off on their phone’s privacy. While the ministry has come under fire for forcing this practice, and said it would stop, it has not yet made those changes. Instead of creating an optional digital service to facilitate these processes and give the users control to opt-out of data collection, Israel imposes these terms on them.4 In describing the harms of dark patterns, Sage Cheng, Design and User Experience Lead at Access Now, states that, “User experience and interface design should aim to inform and empower people, not violate and abuse their human rights.” It should not, she continues, serve “surveillance capitalist incentives that silently steal people’s personal data.”5 Behind the veil of this digital solution’s “convenience” and “access” lies the reality of Israel’s apartheid state, where an advanced and resourced military is able to successfully exploit the digital illiteracy of the majority of the Palestinian population, primarily the elderly and working class, to further entrench its dominance.

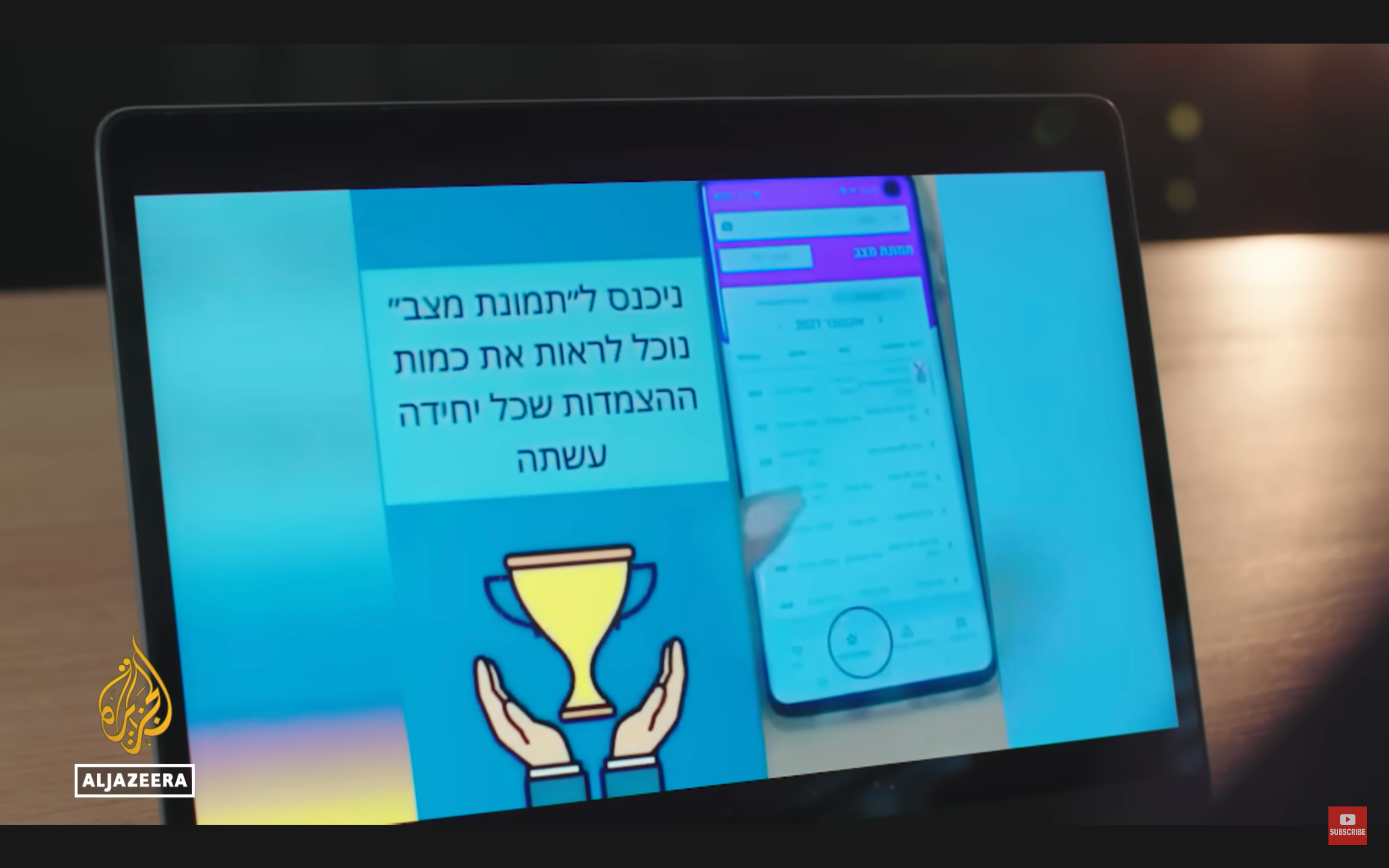

There are many facets of manipulative design tactics in oppressive surveillance regimes. Israeli forces have also managed to design a way to gamify data collection with incentives and rewards. Soldiers stationed in the West Bank are instructed to use a smartphone app called Blue Wolf to collect biometric data on Palestinians during raids and patrols. There are countless videos of soldiers carrying out night raids, while people are sleeping in their homes, and taking photos of the occupants, including the elderly and children. The app uses facial recognition to match the photos with a database of Palestinian faces; it then uses a color-coded system to tell the soldier whether to arrest, detain, or release the person. If the AI algorithm doesn’t recognize a face, the soldier can insert the photo into the database, further expanding it. Soldiers are incentivized to compete with one another and rewarded with prizes the more photos each unit collects. Ori Givati, the director of Breaking the Silence, an organization that gathers testimonies from soldiers using the app, states that “Palestinians are pawns in our video game.”6 Great design is used to make the app’s user experience seamless and even engaging for bored soldiers. Just like any game, this one manipulates the psychology of its users by giving them a dopamine hit every time they collect a data point on a Palestinian. This allows Israel to grow its biometric database of the Palestinian population at scale. The danger is that it is done without any checks and balances or Palestinians’ informed consent, further endangering their lives and violating their right to privacy.

Screenshot of the Blue Wolf app from Tariq Nafi in “How Israel Automated Occupation in Hebron,” Al Jazeera, The Listening Post, May 6, 2023, YouTube video, 25:20, link.

The public and private sectors have strategically collaborated to craft an automated digital apartheid wherein Israeli designers and engineers are free to implement a political agenda that has been part of Israel’s DNA since its founding. From their ivory tech towers, they have set up a surveillance network that provides the most sophisticated user research on their target audience. The most challenging aspect of designing a system is understanding user behavior, and the apartheid state has truly perfected this feedback loop. Israel’s all-seeing eye now has the potential to live in the unwilling pocket of every Palestinian.7 The digital user interfaces of its surveillance infrastructure are designed with the goal of gathering information to target a population, either by rewarding the aggressors or deceiving the victims.

A post-October 7th Palestine/Israel is ushering in a new era of surveillance aided by AI. More oppressive and dystopian measures will be taken in the name of security and self-defense. We see these measures unfolding today — from AI-driven software that surveils individuals on kill lists and bombs them in their family homes in Gaza, to military cameras that point directly into people’s houses in Hebron in the West Bank. These mechanisms have proven to be exceptionally immune to international human rights laws, as Israel continues to maintain its hegemony while purporting to provide safety for its own population. But, as history has taught us, safety will never be guaranteed to the oppressor as long as they continue to subjugate another population.

Further References

Access Now. “Exposed and Exploited: Data Protection in the Middle East and North Africa.” Access Now, last updated October 20, 2023. Link.

Amnesty International. “Automated Apartheid: How Facial Recognition Fragments, Segregates, and Controls Palestinians in the OPT.” Amnesty International, May 2, 2023. Link.

Kirchgaessner, Stephanie, and Michael Safi. “Palestinian Activists’ Mobile Phones Hacked Using NSO Spyware, Says Report.” Guardian, November 8, 2021. Link.

Shakir, Omar, and Maya Wang. “Mass Surveillance Fuels Oppression of Uighurs and Palestinians.” Al Jazeera, November 24, 2021. Link.